Chapter 3: Jeff Wall, Wittgenstein, and the everyday

September 27, 2010 § Leave a comment

In this chapter, Michael Fried attempts to explain how some of Jeff Wall’s later photographs justify Wall being called an “antitheatrical” photographer that photographs in a “near documentary” way; Wall sees an everyday scene, and recreates it through several different shots and uses “subjects” that are so in character, they should feel like they were the person in the scene first experienced. Fried uses Wall’s Morning Cleaning and Fieldwork photographs as examples this:

Furthermore, Fried argues that Wall’s photos are a renewal or reinterpretation (not necessarily intentionally) of paintings such as the mid-17th century piece Interior with Painter, Reading Woman, and Sweeping Maid:

When compared to this painting, Morning Cleaning has many compositional similarities, as well as sharing the idea of a work of art depicting the “everyday”, with subjects that are oblivious that they are being beheld.

When compared to this painting, Morning Cleaning has many compositional similarities, as well as sharing the idea of a work of art depicting the “everyday”, with subjects that are oblivious that they are being beheld.

Finally, Fried makes a correlation between a passage written by Ludwig Wittgenstein and Jeff Wall’s photographs. The passage, written in 1930 and comes from a volume called Culture and Value, talks about how “nothing could be more remarkable than seeing someone who think himself unobserved engaged in some quite simple activity”. Wittgenstein longs for art that is more “genuine” and “in the moment” than theater, but also contradicts himself by admitting that when one sees the everyday played out in front of their eyes all the time, no special attention is paid. Wittgenstein then makes a very valid point; one that I appreciated reading as a way to understand how people define what art is:

“…only the artist can represent the individual thing…so that it appears to us as a work of art; (art) rightly loses it’s value if we contemplate it singly and in any case without prejudice, i.e. without being enthusiastic about it in advance. The work of art compels us – as one might say – to see it in the right perspective, but without art the object is a piece of nature like any other and the fact that WE exalt it through our enthusiasm does not give anyone the right to display it to us.”

Fried makes the point that art makes us see the ordinary. Jeff Wall’s job is to interpret the everyday and make it meaningful – or not. His job is to recreate the “everyday” so that it is art for us to look at and think about and interpret. He goes on to discuss how certain Wall photographs contain subjects that “refuse to be beheld”; Fried cites photographs such as Untitled (Forest), where the humans in the photograph are fleeing the scene and Untitled (Night), where the beholder has to work hard to perceive the image and as a result, is resistant to being beheld:

Week two: Terry Smith, Leshem and Wright, and a questionnaire on “the contemporary”.

September 14, 2010 § Leave a comment

During a slideshow presentation in my Image and Text class today, we discussed On Kawara’s date paintings, shown above. The dates in these paintings are chosen according to when Kawara finishes the paintings. From my understanding, these paintings are a postmodern reaction to the idea that there is too much value put on periods and dates in art history, and the actual content of an art piece in a museum comes second. Matt Siber made the comment that the concept of these paintings are interesting at face value, but don’t really command the viewer to stare at them for very long because, well, they are black and white paintings of dates. He then went on to explain that it isn’t enough for artists today to make purely conceptual art, and it isn’t enough for artists to make purely aesthetic art. Artists need to find a balance in between the two to be successful.

During a slideshow presentation in my Image and Text class today, we discussed On Kawara’s date paintings, shown above. The dates in these paintings are chosen according to when Kawara finishes the paintings. From my understanding, these paintings are a postmodern reaction to the idea that there is too much value put on periods and dates in art history, and the actual content of an art piece in a museum comes second. Matt Siber made the comment that the concept of these paintings are interesting at face value, but don’t really command the viewer to stare at them for very long because, well, they are black and white paintings of dates. He then went on to explain that it isn’t enough for artists today to make purely conceptual art, and it isn’t enough for artists to make purely aesthetic art. Artists need to find a balance in between the two to be successful.

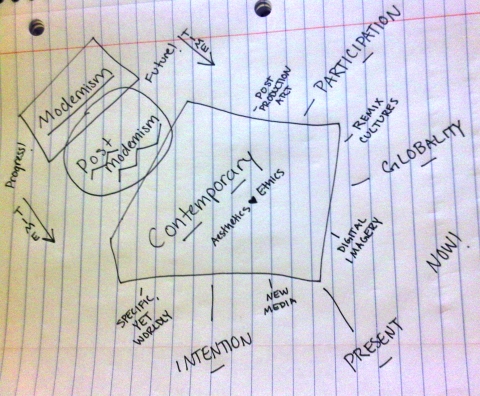

I think this discussion, and his comments, summed up our readings for this week pretty well. I was worried about being able to contextualize modernity in relation to contemporaneity, or visa versa, but once I began to skim through highlighted passages and annotations I made in the articles, everything fell into place.

Pulling from the questionnaire on “the contemporary”, Alberro wrote about how globalization plays a key role in what contemporaneity is and how it is defined. He brings up art fairs around the world, and how the idea of exhibiting art in one location from around the world is one small symptom of contemporaneity. Art collecting and critique is taken from museums and put into the hands of the public through globalism. Alberro goes on to discuss how there is a return to aesthetics in contemporary art, and cites artists that make work that commands participation, and not just spectatorship.

In Leshem and Wright’s review of Michael Fried’s Why Photography Matters as Never Before, it is discussed that Fried’s stance on art and how it must not require us to respond if we are not directly addressed. Leshem and Wright go on to say that, “such a position might be convincing where the ethical stakes of the images are lower”, but in works of art such as Delahaye’s, it is hard to not somehow get involved and somehow feel responsible. It is concluded that Fried values the importance of distance between a photograph and the viewer, so that the viewer is still able to appreciate the photo aesthetically, instead of getting completely lost in large scale photographs that command sadness and, perhaps, guilt.

Terry Smith’s Contemporary Art and Contemporaneity helped me understand contemporaneity the best, in terms of how it relates, but still tries to get away from modernity. It is explained that contemporary art attempts to explain what it’s like to live in the present, and what it’s like to BE in the world right now. I think Smith says it best when he writes that contemporary artists are “commtited to an art that turns on long-term, exemplary projects that discern the antinomies of the world as it is, that display the workings of globality and locality, and that imagine ways of living ethically within them…” and that modern art looked at the future, but failed to look at and contextualize the present. Art that is contemporary marries aesthetics with ethics, instead of one or the other like in the past. Contemporary art is intentional and requires participation.

Something is to be said about Smith’s view that “contemporary” is just a place holder for something not yet named. At face value, “contemporary” just refers to art that is being made now, and “contemporary” could have been used in the past for anything that was being made in that time period. The word “contemporary” doesn’t really refer to anything specific, it just refers to nowness. It would be interesting to see what “contemporary” is called in 100+ years.

“There are three times: a present of things past, a present of things present; and a present of future things”